What is osteochondritis dissecans?

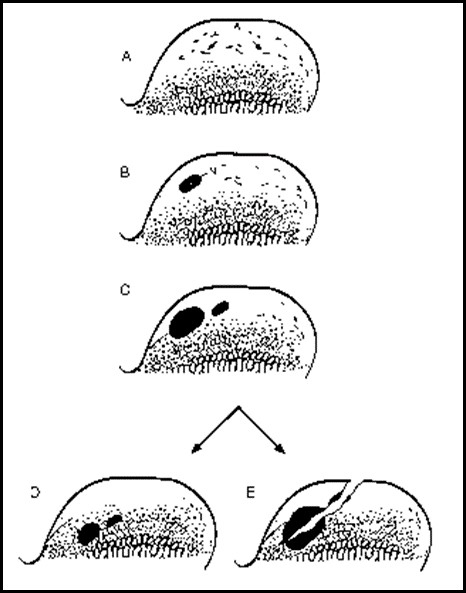

Osteochondrosis (OC) is a developmental condition that arises due to a disturbance in the normal differentiation of cartilage cells into bone as a puppy grows. This is a failure of endochondral ossification which is an essential process during foetal development and development of juvenile dogs in bone formation from the cartilage precursor. In dogs that grow very quickly, the rapid cartilage growth at the ends of long bones (on either side of a joint) can outstrip its own blood supply causing abnormal thickening of the cartilage. This may then crack off, allowing joint fluid to leak under a flap of detaching cartilage. This gives rise to inflammation (-itis) and further dissecting away of the cartilage flap (dissecans). Thus osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) can result in lameness, pain and subsequent osteoarthritis.

OCD can occur in any joint of the body, but most commonly affects the shoulder, elbow, knee and hock (ankle).

Why does this disease happen?

OCD is a “multi-factorial” disease. Genetic factors are most important, with strong breed predispositions, particularly in Labradors and giant breed dogs. Different breeds appear to be predisposed to developing the condition in different joints. For example, the shoulder joint is most commonly affected in Border Collies, Great Danes and Irish Wolfhounds, while the hock is more commonly affected in Bull Terriers, Rottweilers and Labradors. Various other factors such as dietary or nutrition problems, high growth rate or calorie intake over the first few months of life, hormonal imbalances and joint trauma can also increase the risk of developing OCD.

How do I know if my dog has OCD?

Most dogs with OC/OCD start to show clinical signs before they are 1 year old, although occasionally (particularly with shoulder OC) signs may present when your dog is older. Clinical signs are variable and depend on the joint affected and the size of the cartilage defect. The most common signs include lameness, stiffness, joint pain or swelling, and reluctance to exercise or play.

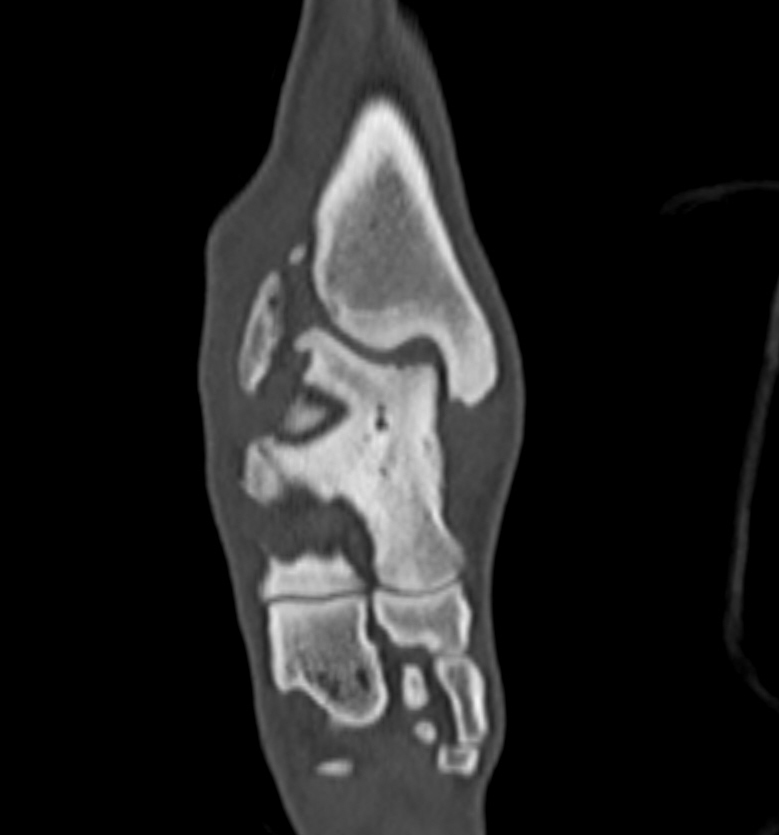

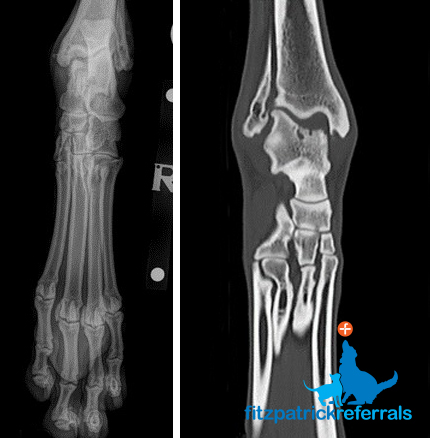

How is hock OCD diagnosed?

OCD is typically diagnosed by radiography and CT scan following clinical examination. Firstly your dog will be examined by one of our orthopaedic clinicians, following this your dog will be admitted to the hospital to allow radiographs of the affected joints under sedation or general anaesthesia. Additional diagnostic imaging using CT scan is very useful for defining the true extent of the lesion affecting the bone, and this can be performed by our advanced diagnostic imaging team. CT scan is necessary if a custom implant is to be manufactured. The cartilage cannot actually be seen without advanced MRI scanning techniques or looking directly inside the joint using arthroscopy.

Your dog will receive one-to-one nursing care throughout the process by one of our nurses from the prep nursing team who are all highly trained and experienced in anaesthesia and sedation. Following diagnostic imaging, your dog may benefit from surgical intervention.

Will my dog develop osteoarthritis?

As soon as OCD starts to develop unfortunately osteoarthritis (inflammation of the joint and associated bones) immediately starts to develop. Once present, osteoarthritis (OA) cannot be cured but can be effectively managed for most patients. Alongside your orthopaedic clinician our chartered physiotherapists and OA team will be able to advise you on management of osteoarthritis and design a rehabilitation plan suitable for your dog. However, it should be emphasised that in the case of OCD of the tibio-tarsal (ankle) joint, no rehabilitation regime can result in normalised joint function without surgical intervention.

How can hock OCD be treated?

Various treatment options are available for OCD in the hock. The best treatment option for each dog is recommended following thorough clinical, radiographic, and possibly CT scan and arthroscopic assessment.

1. Non-surgical management / conservative management

Non-surgical management with drug therapy or rehabilitation techniques may allow some improvement in lameness or pain in the short term, although it is seldom recommended for dogs with OC except where the risks of a general anaesthetic or surgery are considered excessive (e.g. severe heart disease, immune conditions). If the defect left by the cartilage flap is significant, then the exposed bone of the talus bone will rub on the joint surface of the tibia and that too will inevitably endure cartilage erosion.

Five basic methods may be used:

- Body weight management

- Exercise modification

- Anti-inflammatory / pain relief medications

- Nutraceutical supplements (e.g. glucosamine, chondroitin sulphate, pentosan polysulphate, green-lipped mussel extract)

- Physiotherapy and hydrotherapy

2. Surgical removal of cartilage flap / debridement

Surgical removal of the cartilage flap has been advocated in the past. The hope was that the physical ‘irritant’ of the fragment could be removed and the defect may heal by scar cartilage formation. Scar cartilage (fibrocartilage) is less robust than healthy joint (hyaline) cartilage, so although this could in some circumstances result in an amelioration of discomfort which is short-lived, our experience is that the joint will remain abnormal, with ongoing development of osteoarthritis and cartilage wear. We currently only ever recommend this surgery for very small or shallow disease lesions. We may use this treatment in conjunction with the injection of stem cells which have been specifically differentiated from a bone marrow sample to produce cartilage cells.

It should be emphasised that in general the disruption of surface topography caused by a significant defect in the talus bone causes profound long-term debilitation whether the fragment is removed or not.

3. Osteochondral autograft transfer system (OATS) and SynACART™ implant

In the past we have used both the OATS™ and the SynACART™ implant systems (Arthrex, Naples, FL) system to try to ‘fill’ the defect in the talus bone. The OATS technique involves collection of a cylinder of bone and cartilage from a non-contact area of a healthy joint (usually the knee) and transplanting it into a joint affected by OCD in order to resurface the cartilage defect with healthy hyaline cartilage. However, it’s extremely difficult to contour-match the deficit in the talus bone and therefore we no longer use this technique. We do not have an adequate supply of cadaver donor bone in the UK to recommend a size and location-matched transplant from a deceased dog.

At Fitzpatrick Referrals, we pioneered this technique of using a synthetic resurfacing plastic called polycarbonate urethane in the shoulder, elbow, knee and ankle of dogs. This is marketed as a product called SynACART™ and has proven successful for application in the elbow, shoulder and knee of dogs, and in a limited number of cases of ankle defects, but we no longer recommend this implant for this location since matching the surface topography of the defect is rarely possible.

4. Partial joint replacement

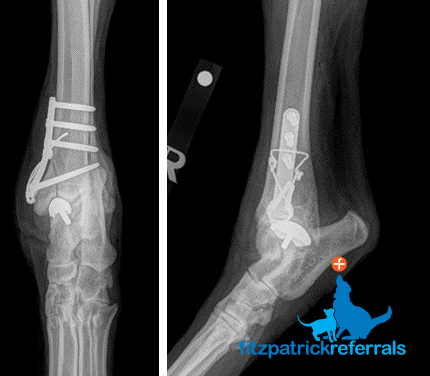

At Fitzpatrick Referrals, we have pioneered the technique of manufacturing a three-dimensionally printed metallic replacement ridge to resurface the talus defect. This implant has a super-smooth articulating surface and an underside made of honeycombed metal coated in a mineral called hydroxyapatite, which encourages new bone to grow into the implant when inserted. Each implant is custom-made from a CT scan of the patient so that it fits exactly.

Access to the joint is achieved by cutting off the side of the tibia bone (osteotomy of the medial malleolus) – which is then reattached using a plate, screws and wire. We have experienced good success with this implant over the past three years, such that dogs can return to full function. There will inevitably be some progression of osteoarthritis and at present, we do not have follow-up in excess of three years post-operatively. A similar implant is now available for human patients affected by this condition.

5. Total joint replacement / arthrodesis

Occasionally in some dogs with long-standing OCD which has resulted in severe osteoarthritis, either total joint replacement or fusion of the ankle joint (hock or tibio-tarsal joint) may be recommended. Total joint replacement is a ‘salvage’ procedure (i.e. it is performed as a last resort where other treatments are likely to be ineffective) and involves replacing the entire joint surface with metal and plastic implants. This can be performed for the hip, elbow, shoulder, knee and hock joints. Total ankle replacement in dogs with either commercially available or custom implants is in its infancy and at this stage we do not have long-term outcome data to report.

An alternative procedure is arthrodesis – surgical fusion of the bones on either side of a joint to prevent painful joint movement. This can be a very successful procedure for painful ankle joints and function can be very satisfactory, albeit that movement of the joint is obviously removed and the patient walks and runs with a mechanical lameness.

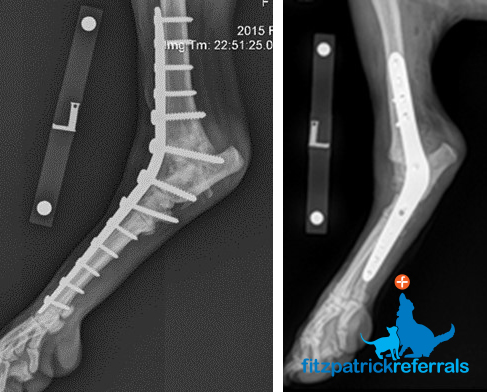

A variety of plates and screw types can be used to execute this procedure, and they can be broadly categorised into a plate down the inside (medial) or the front (dorsal) or the back (plantar) of the ankle joint. We employ either medial or dorsal plates at Fitzpatrick Referrals and we have been instrumental in the development of a number of new customised plate designs for hock arthrodesis which aim to circumvent some of the problems associated with previous repair techniques. In all cases, all of the cartilage of all the joints in the ankle – which include the uppermost highly mobile joints and the lower less mobile joints – must be removed – and bone graft (from the same patient of a donor deceased dog) is used to facilitate fusion.

9 minute read

In this article