What is epilepsy?

Seizures are the physical manifestation of uncontrolled electrical activity in the brain and are the most common neurological problem in canines and felines. They can be very distressing and cause anxiety for you and your pet. All of the cells in the brain communicate with each other using chemical and electrical signals. Seizures are the physical manifestation of uncontrolled and hyper-synchronous electrical activity in the brain.

How can I tell if my dog has epilepsy?

Different types of seizure can occur in animals; most typically ‘generalised’ seizures are seen. Generalised seizures cause a loss of consciousness, involuntary repetitive movements, urination, salivation and defecation. Smaller or ‘partial’ seizures involve more focal areas of the brain and may appear as muscle spasms/tremors, abnormal sensations or even hallucinations. Your pet may exhibit any variation of the aforementioned signs however be rest assured that your pet does not feel pain during a seizure and are largely unaware they are occurring. However, they may feel disorientated and confused afterwards for a variable time period. It is important to give them reassurance and the opportunity to adjust following a seizure. Usually, this involves some TLC and rest.

What is the cause of epilepsy?

Seizures may occur due to an identifiable cause; like intoxication, kidney disease, liver disease, brain malformations, tumours or inflammation (so called ‘symptomatic’ epilepsy). When an underlying cause cannot be identified, primary or idiopathic epilepsy is the presumed diagnosis. In most cases, we assume this is related to an underlying genetic predisposition, but multiple genes and environmental factors are involved in developing epilepsy.

How is epilepsy diagnosed?

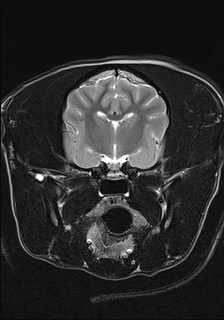

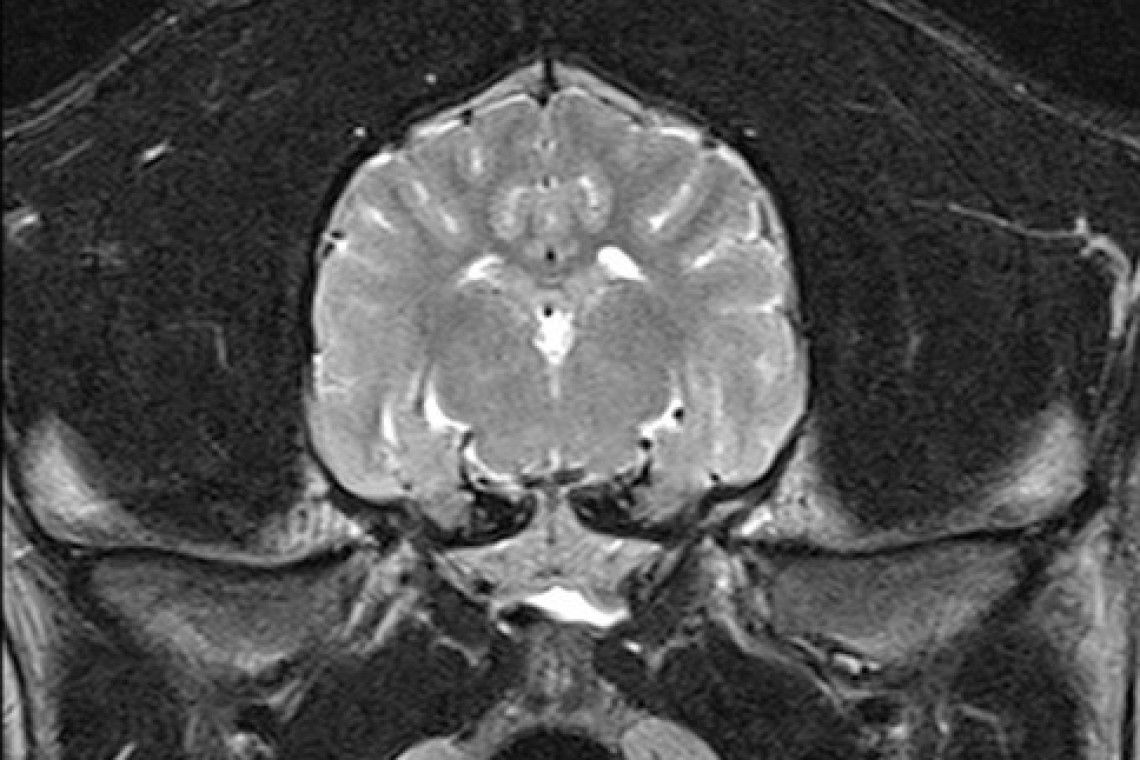

No single test can tell if your pet has primary epilepsy. It is what we call a ‘diagnosis of exclusion’ as multiple tests are required to exclude all other causes of seizures. Typically, a diagnostic investigation is split into two parts; firstly to investigate and exclude diseases where the seizures are caused by a problem outside of the brain, and secondly to investigate and exclude those within the brain itself. Your pet will most likely have a blood sample taken and a urine sample as part of the diagnosis process. Finances permitting, advanced brain imaging via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain may also be performed by our advanced diagnostic imaging team followed by cerebrospinal fluid analysis to exclude structural abnormalities (such as inflammation, or tumours) as a cause of clinical signs. Primary epilepsy is most likely in young animals (1-6 years of age) that are neurologically normal (normal behaviour, normal gait, etc) between the seizures.

Primary epilepsy most likely has a complex genetic and environmental cause. It is rare that vets and scientists have been able to identify the genes responsible in individual animals or dog breeds; however, several dog breeds are known to have a higher ‘familial’ risk of epilepsy, the same may be true for cats. Most epilepsies are ‘poly-genic’, involving mutations in lots of genes. This means that unlike recessively inherited genetic diseases, breeding to prevent epilepsy is very difficult and primary epilepsy can be diagnosed in any individual animal of any breed despite multiple normal generations and litters.

How is epilepsy treated?

It is possible for most epileptic animals to have an excellent quality of life. However, epilepsy is a chronic and occasionally progressive disease that will need to be managed. Rarely, an animal may have a single seizure and not seizure again. An animal that has more than one seizure is expected to have more frequent or severe seizures in the future. There is evidence to suggest that early treatment in the course of the epilepsy can provide a better long-term outcome.

Despite treatment, epileptics are still likely to suffer intermittent seizures. Full remission may occur with treatment, but our goal in the majority of patients is to reduce the frequency of seizures by at least 50% within a four-week period. The severity of seizures should also reduce. 25-33% of dogs with epilepsy will require more than one medication in order to control their seizures. The same may be true for cats. We normally recommend epilepsy is treated when more than two seizures occur in a six-month period.

There are many different anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) available for the treatment of epilepsy. Your neurology clinician or primary care vet will determine which AED is suitable based on the type and number of seizures your pet has had, but also on licensing, formulation, and cost considerations. Two drugs are licensed for the treatment of primary epilepsy in dogs; phenobarbital (commonly prescribed under the trade name EpiphenTM) and Imepitoin (prescribed under the trade name PexionTM). Potassium bromide (prescribed under the trade name LibromideTM) is licensed for uncontrolled epilepsy in dogs. No medication is licensed for cats but we have lots of experience of treating cats with phenobarbital.

We have experience with many other AEDs that are only licensed in people but used in animals. These medications are only used in special circumstances are not recommended in the first-line treatment of epilepsy in animals. The main reason for this is that dogs metabolise these medications very quickly and they are less effective in dogs than they are in people.

With most AEDs side effects of treatment can be expected to occur. These side effects are typically worse in the first few weeks of treatment and their severity may decrease with time. Common dose-dependent side effects include increased thirst and hunger (consequently urination and weight gain), lethargy, panting, hyper-excitability and possibly wobbliness. Your neurology clinician or primary care vet will discuss with you what side effects may be expected with medication.

What can you do to help your epileptic pet?

It is very important to keep a seizure diary for your pet. The diary should include the date, the number of, the duration and appearance and severity of the seizure(s), whether there was any obvious precipitating cause, and whether abnormal behaviour was seen in the period after a seizure (post-ictal period). Sharing these diaries with your neurology clinician or primary care vet will assist them in assessing whether treatment is reaching its goals. In addition, it will help to de-emotionalise the seizure experience if you and your family understand what should be done when they occur.

During a seizure, you should do the following things to protect your pet:

- Move any objects from around your pet that they may injure themselves on e.g. furniture

- Turn off the lights, music and television to reduce environmental stimulation

- Begin monitoring and recording their duration and severity of the seizure

Never be tempted to put your hands in or around your pet’s mouth. Animals may bite during or after a seizure as they may not recognise you. It is understandable that you will want to comfort your pet but only hold them if they have stopped actively seizing and if they are seeking attention. If your neurology clinician or primary care vet has prescribed rectal diazepam this can be administered as instructed if it is safe to do so.

Contact your vet as soon as possible if:

- Your pet is actively seizing for more than two minutes

- Your pet has more than two seizures in a 24-hour period

- Your pet is showing recurrent twitching / tremoring

What is the prognosis of epilepsy?

The prognosis for epilepsy is typically good although it is largely dependent on the number of seizures an animal suffers.

Occasional visits to your primary care vet may be required during the course of treatment. Some AEDs will be metabolised by the liver. This metabolism can increase with time, meaning higher drug dosages may be required to maintain the same concentration of the drug in the blood. Your vet may suggest blood tests every few months to assess the concentration of the AED in the blood, or to assess the function of the liver. How often this is required will be dependent on your pet’s response to treatment.